Compliance Training for girls starts early in life, and it lasts until they choose to stop playing by the rules and willingly pay the consequences. Girls and women are told to speak their minds but to be “nice” while they do so. The pressure to be hot but not slutty is a tricky needle to thread for girls and young women. Perhaps the most challenging expectation to meet is to be assertive and have clear boundaries without being a “bitch”.

Calling anyone a “bitch” effectively and purposefully puts them down and shuts them down immediately. Normalizing the word and expanding the context of its acceptance has not lessened its harsh sound or the sting of being on the receiving end of the insult.

As with many derogatory words, calling oneself and a group of friends “bitches” is often justified as owning the word enough to redefine it as a positive endearment. Once it has been nudged into the funny range, people outside the group chime in and fuel the friendly “bitches” banter. Once everyone is desensitized to the jolly version of “bitch,” it is harder to challenge someone who uses it offensively because it can be defended: “You use the word all the time about yourself.”

Personally, I quit using the word except when I address it in my writing and speaking.

There are plenty of words people have co-opted to become empowering. Pussy hats donned by millions in marches around the world on January 21, 2017, successfully gave the word “pussy” a powerful new meaning in the context of protesting the behavior and language of the newly elected president. Unfortunately, “pussy” is also still used to remind a boy that he is weak and less masculine by some stereotypical standard. I’ll be convinced that the meaning of the word has evolved when droves of teenage boys take a stand and courageously wear pussy hats to let others know they won’t put up with degradation anymore. Ask any guy you know about how the word “pussy” is thrown around, however, and many will say something like, “It’s just banter. Not a big deal.” Many boys and men I interview have shared how enraged and hurt they felt when they were called a “pussy” by a peer, older boy, coach, parent or even a girl. But early in their lives, boys learn to swallow the shame, mask the hurt and attempt to tuck their feelings deep in their hearts.

Most derogatory words feel good to say, especially when venting anger. “Bitch” starts with a powerful consonant and ends with the most impactful digraph. Listeners can’t miss the word when it’s launched, no matter the context or intention behind it. As women, we are all used to strangers slinging derogatory words and gestures at us, sometimes to intimidate us or to let us know we are an offense to them. It is used loosely enough to cover everything from annoyance to hatred of a specific woman or women in general. It is also used by men to vent anger about women who have hurt or rejected them. In groups or public settings, some men like to demonstrate that they can harass or call a woman a “bitch” without experiencing any consequences as a sort of recreational power test.

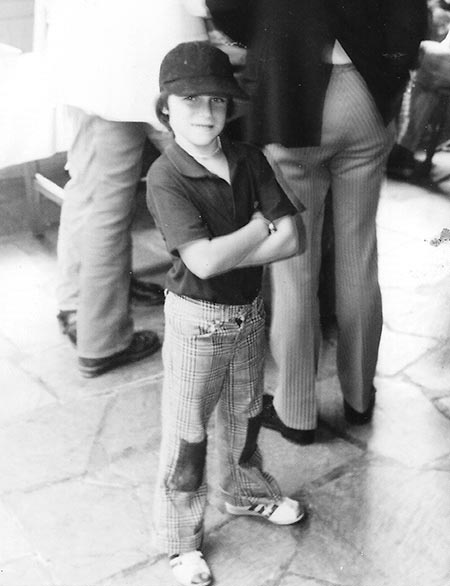

I have been called “bitch” plenty of times by people I know, and by strangers. As the youngest of seven children, my parents and some of my older siblings intentionally taught me to speak my mind and not let people push me around. When a derogatory comment or word is launched my way, I decide if it is safe or worth my time to engage by either unleashing my feisty fire or asking some questions to start a civil conversation. Sometimes my parents and siblings who were responsible for my fierce training as a kid are taken aback when I challenge them about their comments or language. We all say we want our kids to have clear boundaries and have access to fierceness until it is turned on us.

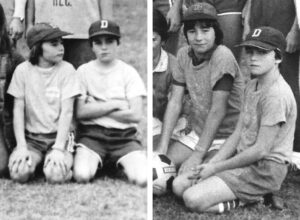

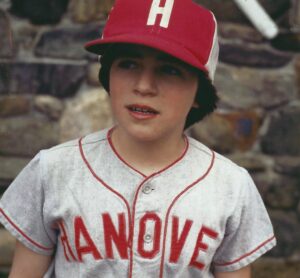

As a young girl, I was fortunate to have women and friends in my life who validated and shared my anger about inequality and the mistreatment of girls. By middle school, I had become a vocal feminist with plenty of smart insights around equality and respect, as well as a number of misguided ideas such as my conviction that I would replace the Boston Red Sox shortstop Rick Burleson and be a mother to ten kids before I turned thirty. Big visions for a kid who was only a halfway decent baseball player and repelled boys with my verbal lashings about their disrespect for women and girls.

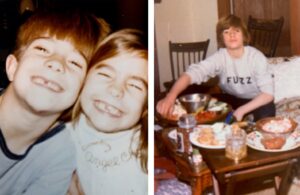

Sometimes it was too exhausting to engage with the sexist guys on my sports teams or in my classes, so I would give the good guys a piece of my mind hoping they would take up the cause. Erik Maurer, my lifelong friend Julie’s older brother, was a frequent target. While happily sitting on the couch watching Hogan’s Heroes and enjoying a bag of chips, Julie and I would round on him with our grievances about specific people or the sexist world we lived in. We didn’t even know the word “objectification,” but we witnessed it daily in school, sports, shows, movies, advertisements and in the workplaces we observed and heard about.

Erik (aka Fuzzy) has always been one of the best of boys and men; I consider him to be a brother as much as a friend. That poor guy was the recipient of our rants about all the wrongs the boys and men of the world were inflicting on girls and women. And he would listen, even though, in those days, pushing pause on a remote control, much less having a remote control, weren’t options during his favorite show. Erik understood our points of view, but he would also shed light on the positive aspects of the fellas whose behavior and language we found so abhorrent. As a 9th grader, Erik Yoda Maurer understood that everyone would evolve and grow with time. None of us were surprised that Erik married a strong woman and is the father of three strong young women.

When a girl or woman in your life gets pissed off or outlines her boundaries, I encourage you to pause and appreciate her courage rather than calling or thinking of her as a “bitch” or any other name with a similar flavor of degradation.

A common form of socially acceptable blowback is to point to hormones as the cause of our anger or disobedience. People claim girls are “bitchy” because they “must be getting their period” (whether that is in the next few days or in the next four or five years). People of all genders attribute female anger to being premenstrual, menstrual, recently menstrual, pregnant, post-partum, perimenopausal, menopausal or angry about no longer having a menstrual cycle. These comments have made me salty for decades regardless of whether I was years from having a cycle, at any time in my cycle or years past those cycles. I am a jolly person most of the time, but if you cross my boundaries, I will let you know in a firm, clear manner. That doesn’t mean that I’m a bitch, and it doesn’t mean that I’m hormonal. It turns out that sometimes I am just plain pissed off.

Special thanks to Nicola Smith for her keen eye in editing.

Cindy love this, and you as always!! I think you should be recording these and have them as a podcast! I have the pleasure of knowing your voice, and your animated wonderful way to story telling – others would love it and I believe it would expand your impact. Xoxo

Thanks Jane. I am working on short videos for educational topics and some personal. You will soon be haunted. A lot of projects are juggling, but the vision is in motion. Thank you for reading and being such a supporter.

Cindy

Thank you Cindy for thoroughly contemplating this and for articulating it so well.

????????

Cindy, This is fabulously well written and to the point with humor. I agree, record it!

Lindy

Spot on Cindy! Keep ‘em coming. Cheers

How well I remember that feisty child! Those drawn eyebrows under the baseball hat. It’s so lovely to see that determination and mischief blended with wisdom and equilibrium. I’d subscribe to your podcast in a heartbeat. Until then I’m reading your words as fast as you can put them down.

Cindy, your articulation and humor are such a breath of fresh air. I’m in awe of your frank, wise and open approach, keep it up, we need more of you!