Finding Balance in the Positive Pierce Family

Being positive is clearly the way to go in life, but there are some benefits to taking a moment of reflection before moving on. As the youngest of seven kids, I was marinated in optimism. Our parents were all about the power of positive thinking. The five oldest siblings were close enough to being adults that my sister Sarah and I relied on them as part of our parenting team. Most of them participated in the indoctrination of positive thinking.

Our parents were champions at finding the good side of life, and I feel blessed to have been raised by such wonderful, positive people. They both experienced difficult things over the course of their lives, including the loss of two children before Sarah and I were born. Moving on was necessary for their emotional survival, and they made a conscious decision to focus their energy on making the future better rather than dwelling on the past.

The wisdom and big picture view earned by raising so many kids brought my parents to an impressively efficient approach to moving on. Their recipe for optimism training included a base broth of enthusiasm blended with equal parts gusto and good cheer, topped off with a generous dollop of denial. Our team of parents and siblings didn’t have much patience for little kid nonsense such as dwelling on or even considering the downside of an experience. The message was that salty or snarky kids missed the fun. If the wee ones wanted to join the Pierce Family reindeer games, we had to bring our jolly selves to the field.

Even if we had a legitimate injury or setback, there wasn’t much room for complaining. When we were hurt or sad, there was a collective effort to hustle us along. This approach worked for many situations and effectively influenced our overall cheerful dispositions. There were times, however, that I could have used just a minute or two to feel the spectrum of emotions before speeding off to Happy Town. They rightfully believed that whatever we focused on would expand.

It was inevitable that things would get out of balance if we kept sailing by some important emotions and leaning a little too hard on denial. As the youngest, I guess it is no surprise that I would be the one to put my foot down and question the denial of my full range of emotions. I have grown into an adult with a generally positive spirit and zero hesitation to express displeasure, especially when people try to boss me out of my true feelings. While this trait is occasionally problematic, it also serves as a natural repellent.

When adults tried to talk me out of feelings when I was young, I found myself seeking the input and perspective of other anchoring adults. Luckily, two of my siblings and my fleet of sisters-in-law helped me get perspective. They affirmed that I could be a jolly, positive person who also had the right to feel angry and frustrated. They encouraged and supported me when I vocalized disagreement. They cheered me on to speak up about any of my true feelings and encouraged me to question the put-on-a-happy-face rule in our family.

When I shared my young adult struggles with my dad (almost flunking a class, being passed over for a job or struggling with a breakup), he would immediately pop open his big suitcase of silver linings and display all the possible solutions and reasons to be grateful. I tortured him with my crying. His attempts to put out the emotional fire as fast as he could were no longer effective. I set some clear boundaries by becoming a righteous crier. To his credit, he had already been through endless conversations of the same flavor with my six older siblings; he knew these moments would soon evolve into pesky little blips in a matter of a few years. I would fight to stay in my moment, “Dad!! I am going to cry because I feel sad. I will find the bright side tomorrow or the next day, but for now I am going to be sad and have some tears.” This was tough on the old jolly maker.

My mom was no slouch in her ability to hurdle over sadness. When I had a knee injury my junior year in college, it felt severe enough that I knew my soccer season was over and that I would miss the beginning of the ski season. My mom happened to be attending the game. When she found me crying on the bench, she snorted, “For goodness sakes Cindy, it’s not the end of the world!” My hissing reaction made it clear that I was not quite ready to make chicken salad out of chicken sh%#, and she backed off.

My injury ended up being a great gift; I spent the next few months reading books, taking physical rehab to a level I had not yet known as an athlete, practicing meditation and growing into a more thoughtful person as a result. However, this required me to be emotionally vulnerable in order to reach a deeper understanding of myself. Setbacks and failures usually turn out to be sneaky gifts. New and interesting people enter my life, my purpose becomes clearer, and a positive new direction seems to align every time, but I am certain that I cannot absorb the full benefits of setbacks without a period of reflection.

In developing my own approach as a parent, it has been handy to sample the ingredients of both my parents’ recipe and that of our siblings’ as they started families. Bruce and I continue to mix, test and tweak our recipe to help guide our three kids. While we do the best we can with what we know at each stage, there is plenty of fuel for their feedback (of which they have plenty). We encourage them to keep a list of all our glitches to edit if they choose to embark on adventures as parents or do some time on the couch to sort out the recipe we conjured up. We believe a balance of forward motion and reflection is essential, but who knows how that will pan out with our kids. They will surely let us know.

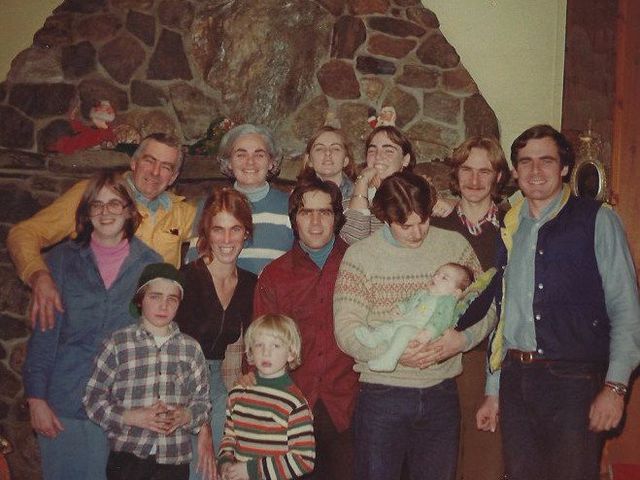

Photo note: For years, I felt badly that I ruined this family photo. I had been crying because the adults trying to make me take my baseball cap off for the photo. When I look at the photos now, it seems that there are a few elements that bring this photo down, particularly the fashion and hair choices of our entire family. Tough decade.